Interactive Dance Music I

November 2, 2020

Objectives #

Building on last year’s Max device, Blue Space, I would like to continue exploring technical solutions for electronic music performance. Blue Space provided an easy way to generate a granular backing track / effect for instrumentalists, with a simple set of grain controls. In this new project I would like to use a dancer’s movements to generate music, extending the ‘ease of use’ theme from Blue Space. I find the relationship between music and dancer fascinating because it makes the dancer into an instrument without necessarily introducing to them to the mechanics of how the music is produced. This means the dance will be an exploration of how the body effects sound, and that the dancer may have to rethink their movements; disrupting established patterns from the previously one-way relationship between music and dance.

Practical Work #

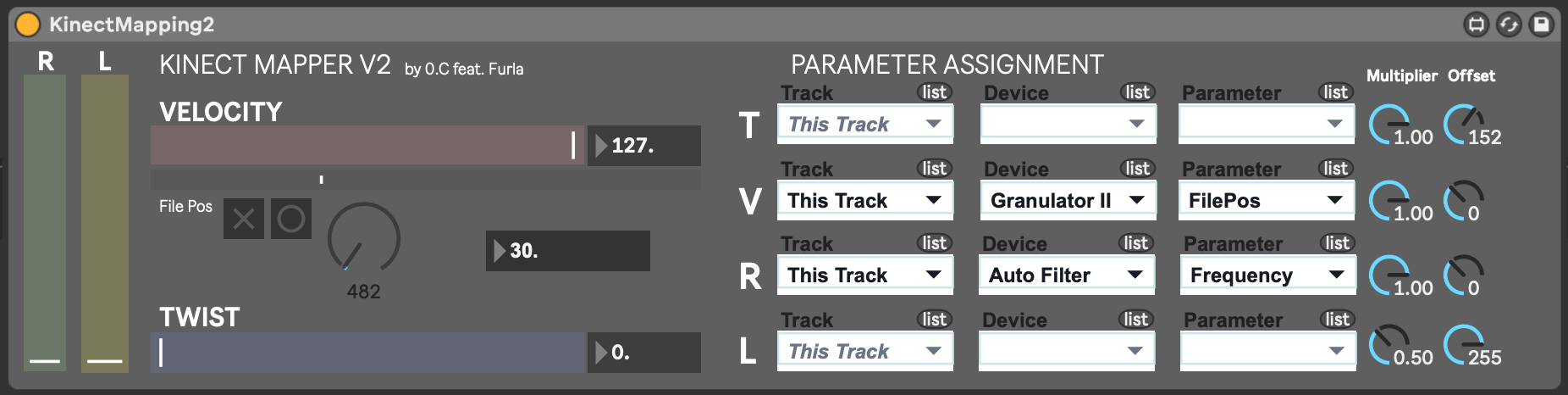

The inspiration for this idea comes from the V Motion Project a commercial project from V Energy NZ. The video depicts a MIDI interface projected onto a wall, controlled by skeleton data recorded by a Kinect facing the dancer. This turns the dancer into a MIDI controller with parameters mapped to joint coordinates (x, y, z for hands, head, etc). I acquired a Kinect a week before term, and so immediately started on ‘practice-led research,’ getting the data from NI mate (the only up-to-date Kinect driver for Mac) into MaxMSP to control Blue Space. I mapped the left and right hand X coordinates to sample positions in Blue Space allowing easy control for the grain window. I made this into a Max for Live patch allowing parameters to be easily mapped to midi or audio effects in Ableton to explore the V Motion Project style of applying the Kinect to existing projects.

Limitations of Direct Mapping #

Mapping the Kinect revealed the limitations of its use as a midi controller, parallel to the V Motion Project; the piece is pre-written so only certain motions correspond to it, requiring a set of movements – a choreography. I explored this by testing the direct application of mappings to a dancer the weekend of the 24th October, with Marguerite Luna from l’École Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq in Paris, whom I went to high school with. Having prepared a number of instruments to evaluate her use of the system, I discovered that direct control over the music using triggers for notes was unwieldy and difficult to incorporate into a natural choreography without significant preparation on a single piece, similar to the use that Chris Vik makes of the Kinect. As such, an Operator patch being modulated using Auto Filter and Ring Modulator frequency proved much more natural, reacting quickly and working with Marguerite’s improvisatory style. Perhaps the most interesting test was the mapping of velocity to sample position in Granulator II – file position progressively incrementing based on current velocity, making Marguerite progressively dance through a sound, while affecting certain parameters. While this could add more physicality to DJ sets & midi performance, it limits the freedom of the dancer and the music, not being an exploration of how the body effects sound, nor making the dancer into a true composer.1

Unfortunately, the amount of time needed for each test and the design of the instruments in tandem with the complications of working with a dancer in-remote due to COVID eventually led to the idea of recording dance videos and analysing the motion-capture data to correlate waveform features and generate real-time audio.2 This is the current focus of my research, and this post will be followed up with a breakdown of approaches – Markov vs. Deep Learning, waveform vs. symbolic – before Christmas.3